For years, as a college professor of sustainability, I thought that the amazing efficiency of our industrial food system was due to clever technology powered by energy-dense fossil fuels. But then, spurred by the Covid shock to the food chain, accelerating climate change disasters, and deep research into whole food systems, I came to see a surprisingly different economy of scale:

Really? But how could that be? Everybody knows that a single tractor does the job of a hundred gardeners. Further, that the average supermarket has 43,000 thousand items under one roof. All resulting from a billion acres of industrial harvest. How could that be inefficient?

The short answer is that most of the seeming efficiency is lost or wasted along the 1,500-mile supply chain that converts maybe 5% of field harvest into the food that makes it to the consumer’s fork. All while wreaking enormously costly economic, social, and environmental damage, as well as massive post-consumption harm to the nation’s health and security. Yet you won’t see the full scope of these outcomes until you consider the food system as a whole.

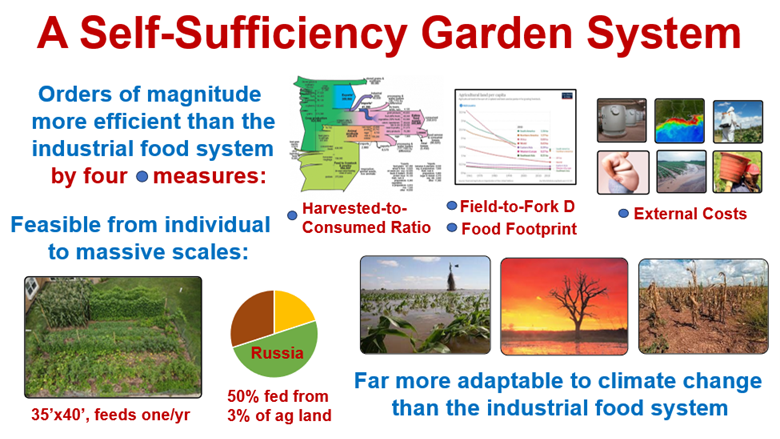

Enter what I call Ultra-Local, Full Circle, Self-Sufficiency. Fully grasping why it’s so much more efficient, feasible, and climate-change adaptable—compared to the industrial system—calls for a systematic journey into mental re-calibration.

The foundation

For starters, what exactly is “ultra-local” food? To be sure, the term has been floating around for a while, but only as another way to refer to simply local food. Which means it’s usually grown at least fairly close to the point of consumption, on small farms, using at least somewhat sustainable methods. I say usually because it often falls well short of those expectations.

But when I say ultra-local, I mean something quite different. Namely, that it’s grown in your own garden, which is decidedly much closer than a local farm. In addition, ultra-local involves more than just planting and nurturing balanced-diet crops. It also means harvesting and prepping them yourself before eating them, closing the full circle of all five steps that you don’t get even if you buy from a farmers market. In turn, that circle of connection—especially when repeated at some length—enhances a second, even more powerful circle: it brings you closer to the earth, yourself, and others. Hence the empowering value of ultra-local and full-circle.

And finally, it is ultra-local combined with full circle that drives the third element: what I call self-sufficiency gardens. That’s another term I’ve found means different things to different people, though none of the other meanings fully match mine. Nevertheless, an Amazon book survey in late 2024 indicated a steadily rising level of interest. It listed just five books on self-sufficiency gardens published from 2010 to 2017—that is, either as stand-alone garden books or as a gardening chapter in books on homesteading. Then eight more appeared from 2018-23. Then, in 2024 alone, ten more popped up. Self-sufficiency gardening was HOT, and it’s still smoking.

The perception reset

Given the disconcerting—many would say alarming—rise in global food insecurity, it couldn’t have come at a better time. Yet it’s a development I’d unknowingly been preparing for over many years as a gardener, botanist, USDA-funded crop breeder, sustainability innovator, university professor, and global thinker. For me, it all came together in 2021, when my mind startled me by linking Morgan Spurlock‘s 2004 documentary “Super Size Me” to the industrial food chain tumult prompted by Covid. That connection inspired me to launch a detailed, comparative study of industrial and gardening food systems. How my thinking has unfolded along the way is a story we’ll explore through later posts.

The upshot: I began to realize that we urgently need a robust alternative to the faltering industrial food system. Not only to provide relief from the annual trillions of dollars worth of industry damage but also to establish an effective buffer against the ever-more frequent and intense climate change catastrophes.

That said, I hereby propose a food system anchored by self-sufficiency gardens, supported by community food webs, in turn complemented by more distantly-sourced foods. This tri-partite system—intended to provide, respectively, a ratio of 50:25:25 percent of our food supply by 2050—rests on five premises.

Deeply re-imagining the global food system

I. The most accurate, useful, and comprehensive understanding of food, which if implemented would benefit the greatest number of people around the world, will come from measuring the performance of food systems as a whole, rather than isolated parts of them. For instance, most food system analyses focus almost entirely on production, and mainly on calorie-rich staples.

II. Food sustainability strategies fail to consider garden-based food systems, despite compelling indications of their effectiveness. Russia, for instance, produces 50% of its food from household gardens.1 (Never mind its misadventure in Ukraine; it’s been largely feeding itself with those gardens since before the tsars). Garden-based systems are not even on the radar of the World Food Program, UNICEF, the World Bank, Oxfam, or other major sources of food relief. Rather, they endlessly rehash fatuous tropes to juice up short-term fixes, all while global hunger continues to increase substantially.

III. As indicated above, self-sufficiency gardens inherently outperform farms—by orders of magnitude for the largest—as by far the most effective way to produce and distribute food, according to whole-system efficiency metrics. This will come as a shock to virtually all food producers, including champions of regenerative agriculture, organics, and even agroecology. The reason is that we’ve become all too dazzled by outwardly impressive—though grossly misleading—partial portrayals of the industrial system.

IV. The industrial food system cannot re-invent itself to any significant degree, no matter how hard it may seem to try. To be sure, industry leaders are at least superficially aware of their problems, and they do strive to address them. But their solutions are doomed to failure because they’re locked into a business model that pays for only about a third of the societal costs it generates, which chokes off any chance at meaningful change. Externalizing most of its expenses has, for instance, allowed the industry to make its single biggest mistake: irreversibly going all-out on ultra-processed foods, now linked to numerous—and decidedly unsustainable—bad health outcomes.

V. Because of their much greater efficiency, close access to production, and on-site storage capacity, self-sufficiency gardens offer far greater resilience for dealing with climate shocks than the industrial system. Which, due to its enormous inefficiency, is too cumbersome to respond effectively once climate shocks begin to overlap. As a cautionary tale, recall the food system chaos triggered by the Covid calamity. A much more nimble system is required, one that can be feasibly implemented from the scale of the individual to many millions, and in a timely manner.

I first delved into all this in an introductory book Just Grow It Yourself – Home Gardens Outshine Industrial Food, and a complementary website, justgrowityourself.com. Those resources are still useful, but I’ve learned a lot—and a lot has happened—since they were launched in 2021. Now is the time to considerably update and expand those efforts with a series of posts in this forum. Stay tuned.

1Sharashkin, L. 2008. The socioeconomic and cultural significance of food gardening in the Vladimir region of Russia. PhD dissertation, University of Missouri. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://naturalhomes.org/img/food-gardening-russia.pdf

0 Comments