What is Diffusion of Innovations?

It’s one thing to say you want to galvanize a self-sufficiency garden food system (GFS), but it’s quite another to imagine just how that would unfold over time. Fortunately, there’s a well-developed theory, “Diffusion of Innovations,” developed by Everett Rodgers, that explains how, why, and at what rate new ideas or technologies spread through a social system.

The initial innovation that led to this concept was the introduction of hybrid corn in the 1940s as an alternative to the open-pollinated standard. Now, a network of self-sufficiency gardens is being offered as an alternative to the average vegetable garden and the industrial food system (IFS). Both innovations represent a significantly different way of producing food, with both starting in Iowa. The following summary illustrates how the main features of this process would be applied to gardens and ultimately an entire food system.

The innovation itself

So to begin with, what’s so innovative about what I’m offering? After all, there are already numerous ways to garden, including how to achieve self-sufficiency therefrom, most notably in homesteading. However, homesteading aims to be off-grid not only in food but also in energy, water, and sewage treatment, so it’s too demanding for most people.

What makes my approach innovative is a unique combination of features I’ve yet to see fully matched by any other gardening system, although a few versions have some elements of it. I’ve described it previously, but for those seeing this thread for the first time, I’ll summarize it here. There are not just one, but two levels of novelty, beginning with the full scope of self-sufficiency gardening itself:

-

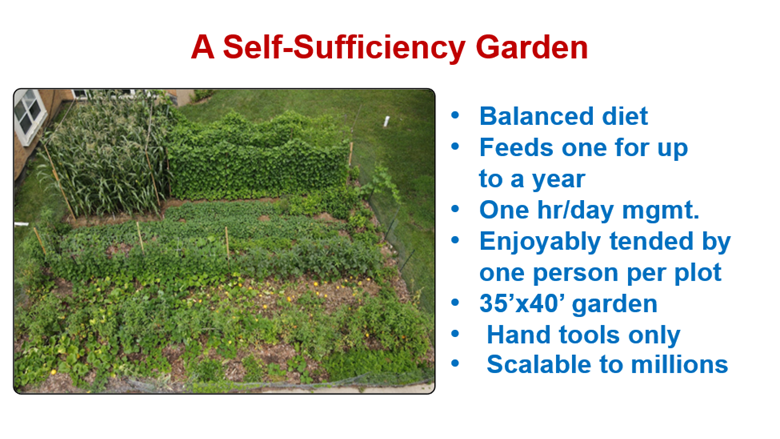

Being able to enjoyably grow a year’s supply of food per person—on a 35’x40’ plot—in an hour a day, using hand tools only.

-

Growing enough variety to provide the vitamins, minerals, fiber, protein, and carbs needed for a fully balanced diet, not just the usual watery veggies.

-

Completing the “full circle” of the gardening experience—planting, nurturing, harvesting, prepping, and eating—on a continued basis.

-

Eating only from one’s garden for an extended period of time, starting—for beginners—with a day, then up to a month, and eventually up to a year.

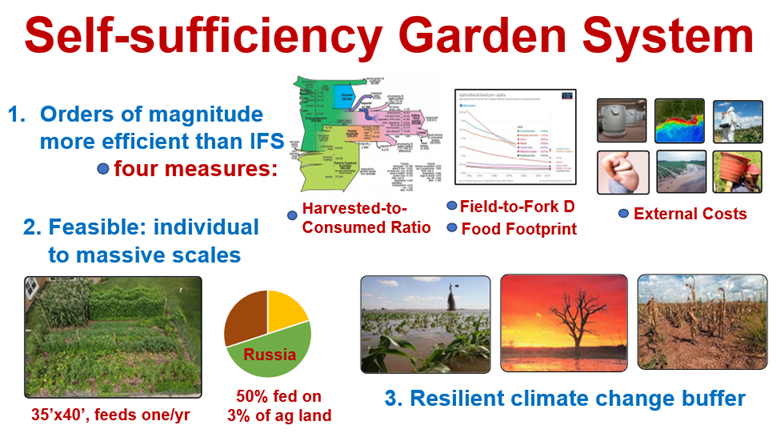

The second level of innovation extends self-sufficiency gardening to a whole food system that is far more efficient than the industrial system. Again, I’ve yet to see another fully developed concept of how any other version of gardening could lead to an entire system of food production and consumption at a massive scale. At most you’ll see grossly incomplete references to organic or regenerative/sustainable agriculture. The GFS is thus an innovative whole system technology distinctly different from the IFS, farm-based agriculture, and typical American gardens.

Elements of diffusion

Characteristics of innovations

In general, the GFS meets Rodgers’ criteria of innovation, as it features:

-

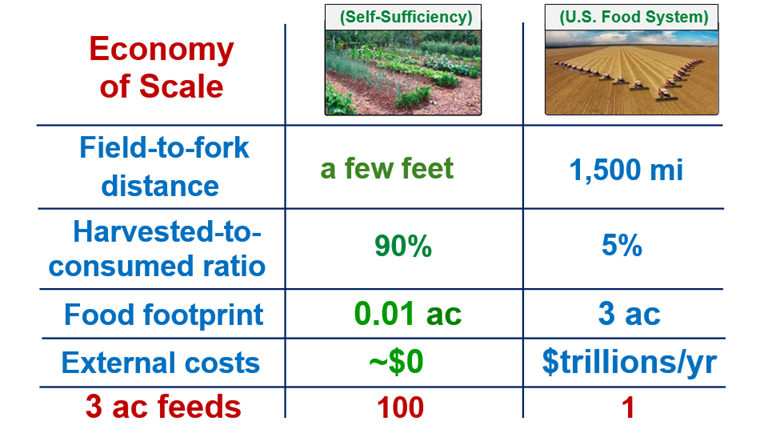

A considerable gain of efficiency – As just mentioned, the GFS is enormously more efficient than the IFS in field-to-fork distance, produced-to-consumed ratio, food footprint, and external costs.

-

Compatibility with the previously existing system – 42% of U.S. households already have food gardens that could easily be ramped up to greater levels of self-sufficiency while inspiring beginners to start up new gardens.

-

Ease of adoption – 20 million WWII victory gardens were scaled up to produce 40% of the nation’s vegetables within a couple years, on short notice, and with little and inexpensive gardener training.

-

Ease of testability – Victory gardens’ contribution to the U.S. food supply was closely tracked by the USDA; today, its 2,900 Extension Offices and 100 university affiliations are ideally set up to document the efficacy of self-sufficiency gardens.

-

Potential for continued development and improvement – Hundreds of gardening books, videos, articles, and webinars provide limitless potential for adapting the basic concept of self-sufficiency gardens to individual preferences.

-

Easily observed results – The positive effects of home gardening on health, food budget, self-empowerment, and social well-being are already well documented.

-

A small core and large periphery – The core is existing gardeners, who are well positioned to ramp up to a large periphery of self-sufficiency garden adopters.

-

No disruption to routine tasks – This is especially true for the surprisingly reasonable time requirement, which turns out to be one of the most innovative elements of self-sufficiency gardening (see next).

Lack of significant barriers

Potential barriers, and why they’re not deal-breakers, were addressed at length in the April 1 and 13 posts. Summarized, they are:

-

No excessive time requirement – As I’ve previously documented—with a season-long, daily activity/time log—it took me, at age 72, only about an hour a day to grow a year’s supply of food—over 1,000 pounds of vegetables.

-

Producing enough protein and calories in a garden –With 70% of our population overweight and 43% obese, current baseline standards for these nutrients are likely skewed to excessively high levels. I suggest eating from a self-sufficiency garden planted to about one-third each of protein-rich, calorie-rich, and watery but otherwise nutrient-rich crops, then closely monitoring your health to achieve optimal results.

-

Ramping up a 35’x40’ garden to serve a family of four – Specific data for that scenario is not yet available. However, the fact that household gardens in Russia provide half of its food on just 3% of its agricultural land indicates that meeting family needs on a very large scale is not a problem.

-

Sufficient storage space – With 2,400 sq ft of floor area, the average American house should not be too challenged to allocate perhaps 5% of that space for stocking canned, frozen, pickled, dehydrated, and whole dry home-grown food. Especially since it will typically be stored in floor space-efficient shelves, whether in pantries or cold storage.

-

Competition from convenient, cheap, and tasty ultra-processed foods – Rapidly increasing concern about UPF links to bad health effects, rising food prices, and increasingly frequent and intense environmental catastrophes are already driving more people to grow more of their own food. More on this point below.

-

No space for a garden – True, people in downtown NY City and the like have no yards and must continue to depend on the IFS. Yet 23% of all U.S. urban area is occupied by lawns with enough space, combined with rural areas, for up to 90% of the population to grow self-sufficiency gardens. Even 50%—which is the goal, after all—would be an extraordinary achievement.

-

Climate change disasters destroy gardens, too – Also true, but because of close-proximity control and in-house food storage, a national grid of self-sufficiency gardens would provide far greater resilience than the 1,500 mile-long industrial food chain with its meager three-day supply of groceries.

-

Even self-sufficiency gardens require external inputs – Yes, they do, and businesses that supply compost, mulch, gardening supplies, greenhouses, education, and even done-for-you services will add many new jobs as the GFS ramps up.

In addition, as the WWII victory gardens demonstrated, training gardeners faces far fewer barriers than training farmers en masse to switch from industrial to regenerative agriculture [ ]. Which is why, when the government needed a quick, effective influx of large amounts of food, it turned to engaging new gardeners, not additional farmers. It also helps that prior adopters (current gardeners) are typically eager to help train and encourage their kindred spirits (new adopters).

Characteristics of self-sufficiency garden adopters

“Google search interest in ‘raising chickens’ has jumped markedly from a year ago. The shift is part of a broader phenomenon: A small but rapidly growing slice of the American population has become interested in growing and raising food at home, a trend that was nascent before the pandemic and that has been invigorated by the shortages it spurred.” — NY Times Feb. 2, 2023.

Research has shown that when a new idea is introduced to a community, the first people to adopt it exhibit a predictable set of character traits. This was certainly true for the introduction of hybrid corn seed to the farming community. Some farmers, because of their innate tendencies—more readily motivated, metropolitan, and empowered—picked it up more quickly than others. For self-sufficiency gardeners, the first adopters will tend to be those who:

-

Are most open to change and new ideas, especially those that center around increasing connectivity to themselves, others, and their surroundings.

-

Are more likely to live in urban and suburban areas, which is where most self-sufficiency gardens will necessarily be located. Surprisingly, rural people are on average among the later adopters.

-

Have the power or agency to create change, not incidentally true of almost anyone who has a lawn, which 80% of U.S. homeowners have. This means that if they have the wherewithal—land, a garden hose, access to gardening supplies, etc.—they’re more likely to start up a garden than those who don’t.

The process of diffusion

As with all new adopters, gardening beginners or upgraders will go through the process of:

-

Learning about the advantages of a self-sufficiency garden.

-

Becoming intrigued by the prospect of enjoyably supplying themselves with up to a year’s worth of a balanced diet.

-

Deciding to try it out.

-

Following through with a trial self-sufficiency garden.

-

Adopting [self-sufficiency gardening] as an ongoing habit.

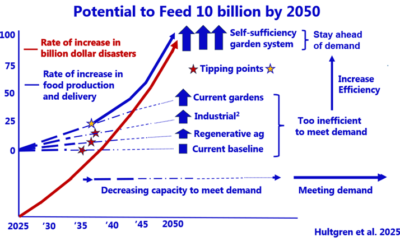

A number of increasingly compelling factors will accelerate this process, though it’s hard at this point to tell which will bring things to a head first. If I were a champion of the IFS desperately trying to preserve business as usual, I think I’d be most worried about the unending parade of bad health effects linked to ultra-processed foods. Given that the industry puts about 75% of its business in that basket, with the goal of increasing it to 90% by 2028, I just cannot see any way out for them. They’ve really painted themselves into an existentially-threatening corner. About the most they can do now is remove or hide some of the more toxic ingredients while trying to retain ultra-convenience, irresistible taste, and artificially low cost—a daunting challenge for most UPFs.

However, UPFs could well turn out to be a moot point if the now much-weaker FEMA first reaches a point where it can no longer deal with the steadily increasing frequency and intensity of environmental disasters. Or if ill-prepared states, to which FEMA is already trying to punt responsibility, have to take over crisis management. Or if insurance companies reach their limits for damage coverage. All of which is being hastened by a mindless trade war that’s hitting small- to medium-sized farms1 harder than any other sector.

These are only the most alarming signs of distress for the reigning food system. Together, they make it all the more urgent to adopt a system that offers a better future.

Decisions, decisions

Most important about deciding to start a garden is that it be chosen freely, implemented voluntarily, and enjoyed. The decision cannot be imposed by those in positions of power or influence (from parents to governments), or by some collective entity, even if democratically voted for. For gardening to work at all, the decision to do it must be freely made by the individual; disgruntled gardening, especially by kids, is a non-starter. That said, friendly, respectful enticement, as well as leading by example, is very much in order.

Stay tuned for further parameters of diffusion of innovations.

1Irby, M, and Cleveland, J. 2025. In its war against small farmers, Congress says the quiet part out loud. The Hill.

0 Comments