Rate of adoption

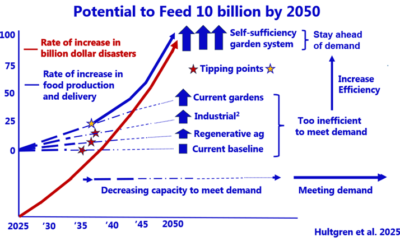

All successful innovations go through an adoption curve, in which the new technology, practice, or idea reaches a critical mass. After that, it becomes self-sustaining, at least according to theory. But not all innovations are successful. For instance, many predicted that sustainable/regenerative agriculture, which is invariably framed as innovative, would be wildly successful. Yet even after decades of trying, it’s never accounted for more than about 1% of wholesale U.S. food sales. Or 6% if you count USDA organic, which is more a compromised list of don’ts than a farming system. Self-sufficiency gardens have much greater potential to reach a critical mass. Why? To briefly reiterate from previous posts, they have:

-

Demonstrated impressive efficiency and scalability, as in Russia’s household gardens providing 50% of the country’s food on just 3% of its agricultural land. Another example: Nigeria’s production of 50% of its vegetables on 2% of it’s agricultural land.1

-

The capacity for quick implementation, as indicated in general by U.S. WWII victory gardens ramping up to 40% of the nation’s vegetable production on 20 million gardens—all within just a couple years.

-

A low-cost ease of adoption with minimal technology and training, again evidenced by victory gardens, not only in the U.S. but also in other countries.

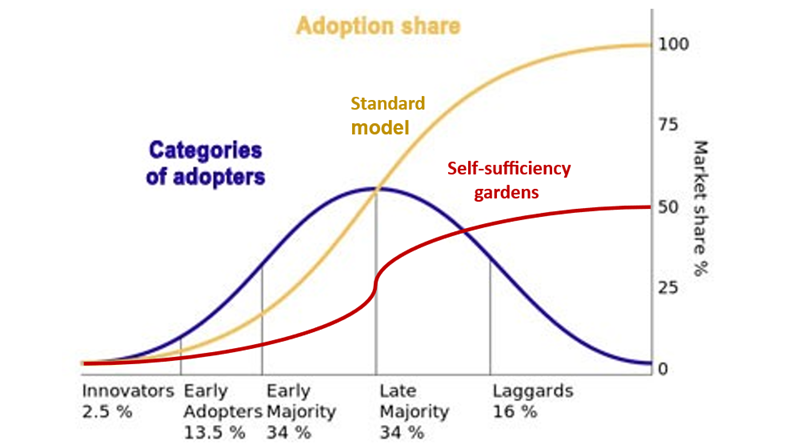

However, the diffusion of innovations model holds that adoption will eventually reach 100%; anything significantly lower than that is considered a failure. By contrast, I’ve said all along that if just 50% of the population adopted a self-sufficiency garden—or if together all types of household gardens produced 50% of our food—it would be an enormous success that would drastically improve the health and well-being of the nation.

Besides, most people in high-density populations like New York City literally can’t have a garden. As well, others are physically unable to or don’t care to have one, so 100% adoption is simply not feasible. That’s why a successful curve for self-sufficiency gardens, despite following an S-pattern, is much better suited to a goal of 50%, with local food streams and industrial comprising the rest. Nevertheless, the categories of adopters within that goal, from innovators to laggards, would likely fall into the same bell-shaped curve as the standard model:

Adoption strategies

Change agents

Go-getters at the leading edge of adoption may come from inside or outside of a pertinent community. Innovation is typically initiated by gatekeepers, followed by opinion leaders, and from there adoption spreads through the society. Gatekeepers include editors, managers, or community leaders who control initial access to information about a new initiative. Opinion leaders are those who, once the gatekeepers have spilled the beans, so to speak, help inspire the larger community to follow.

The question is, who or what is most likely to be the gatekeepers crucial to self-sufficiency gardens, as well as a food production system made up of such gardens? Will it necessarily be influential people, as assumed by standard diffusion of innovation theory? Or will the influencers be eclipsed by catalytic events, including those outside of short-term human control?

In the case at hand, the single most likely gatekeeper will be the editor who choses to publish this Substack thread as a book. Opinion leaders who then pick up on the concept and inspire others to follow may include:

-

Highly-respected “foodie” experts like Michael Pollan and Marion Nestle, or renowned chefs like Gordon Ramsay or Ella Mills.

-

Environmentalists such as Al Gore or Bill McKibben.

-

Mega-social personalities like Oprah.

-

The National Gardening Association (which conducts large, influential surveys on gardening every few years) and other garden organizations.

-

The mainstream and alternative press (including Substack).

-

Government policy-makers. Ordinarily, this block of potential influencers will be among the last, not the first, to hop on the bandwagon, as they are largely in the pocket of the industrial food system. However, the USDA does have The People’s Garden, [ ] although it’s oriented more toward ordinary gardening than food self-sufficiency. But if the government reaches a point where it can no longer rely on industrial agriculture to fully meet the nation’s food needs, as happened in WWII with victory gardens, it could become a powerful opinion leader. (See Event or Situation Incentives, below.)

Once the novelty of starting up a self-sufficiency garden starts to grab some traction, it could be enhanced by any number of interest-provoking schemes. One option: a gardening challenge enabled through a website or social media. It might be framed as an enticing self-competition: “How long, really, could you live on food you’ve grown yourself? A day? An entire week? A month? How about a whole year? Try and meet a level of food self-sufficiency that’s right for you and tell us about it.”

Other people-oriented strategies could include:

-

An incubation period fired up by enduring communication networks. Social media could be helpful, but only if they steadily build awareness. Viral flash-in-the-pan episodes that attract initial widespread attention but then quickly vaporize are not that helpful.

-

Emphasizing direct word of mouth and example whenever possible. Inter-personal networks are far more durable, especially among those who are already connectivity-schmoozers—as the gardening-friendly tend to be—than less personal forms of communication.

Event or situation incentives

As you may have noticed, these are not ordinary times. It’s increasingly likely that diffusion of innovation for self-sufficiency gardens will be energized not by a socially-mediated strategy but an ominous event or situation that alarms people into taking action. As I’ve mentioned previously, the instigator could be ultra-processed foods. Or rising food prices, or—most likely—environmental disasters. Any of which could be Trumped by the trade war and gratuitous removal of vital support for farms, especially the small to medium-sized operations that account for about 30% of U.S. food output. Which of these ticking time bombs might trigger a gardening boom is anybody’s guess, but at some point necessity may be the mother of adoption.

Benefits

Individual

Food gardening in general bestows a broad spectrum of personal, practical, economic, social, spiritual, and environmental benefits, as most gardeners will readily attest. However, a self-sufficiency garden—as defined throughout this thread—confers additional returns, namely:

· A balanced diet. Again, the average American garden, though adequate in vitamins, minerals, and fiber, is low in protein and energy.

· That it’s structured so an individual can raise a year’s worth of food on a 35’x40’ plot in an average hour a day, using hand tools only.

· An enhanced level of self-empowerment derived from eating only from your garden for an extended period of time, which goes beyond supplementing grocery store fare with garden vegetables.

· The additional degree to which you feel connected to the earth, yourself, and others as a result of sustaining yourself solely from your own efforts. It’s an effect that only really begins to sink in once you’ve experienced it for at least a month straight.

Collective (local to global)

-

When fully developed, a quite substantially greater level of self-sufficiency and food security in the face of climate change and regional conflicts. More on this in the next post.

-

As mentioned before, mitigation or removal of massive health, economic, social, and environmental damage and externalities wrought by the industrial food system. In fact, trillions of dollars worth, every year.

Costs

Individual

-

Expenses of seeds and gardening supplies and equipment, though some items are one-time purchases that can be amortized over years.

-

The challenge of appearance when located on lawns in communities that prohibit gardens due to their claimed lowering of aesthetics or property values. Sometimes—amazingly—gardeners have had to mount enduring campaigns to procure the right to grow their own food. Ironically, studies have shown that community gardens, at least, enhance a range of positive social indicators in the neighborhood, including property values. Attractively-designed individual gardens could thus make it easier for doubters to come around. I predict that if, as I expect, a gardening boom happens, neighbor barriers will start coming down.

-

Health issues resulting from chemical pesticides and fertilizers. Some gardeners use them in even greater relative concentrations, with fewer safety measures, than conventional farmers. Easy to avoid by prodigious use of compost and natural pest controls.

-

Not that likely, but worth mentioning: health issues due to vehicle fumes if the garden is located next to a busy street.

-

Labor? Again, not an issue. Contrary to the industrial mindset, the physical activity of gardening is not “labor” that has to be financially assessed as if the gardener were a farm worker. If engaged enjoyably, knowledgeably, and in a way that’s consistent with one’s physical abilities, the exercise and exposure to nature is not a gardening cost. On the contrary, it’s a benefit, as it directly enhances physical, mental, spiritual, and social health. That’s not to say that farm labor isn’t a legitimate expense for farms. Just that its value has to be assessed differently than the nurturing of a garden.

Collective

-

Public awareness campaigns about the benefits of gardening (as described above) to counter the billions industry spends to maintain 75% or more of our diet as UPFs.

-

Subsidies, grants, and the like may help both individual gardeners and community gardens get started. However, we’ve seen all too many examples of people coming to depend on them indefinitely. That’s how, for instance, “farmer welfare” became entrenched, so care should be taken to ensure that doesn’t happen with any form of gardening. Especially since one of the most valuable benefits is self-empowerment, which would be undermined by continued dependence on freebie financing. Ideal would be for newcomers to start up their gardens with their own resources, with the plot size commensurate with what they can reasonably afford, even if it’s initially quite small. Besides, starting small will help ensure greater initial and then continued confidence of success with increasing size.

The wrap-up

Diffusion of Innovations is thus a useful theoretical concept for imagining how self-security gardens could be adopted over time. Even if they end up producing “only” 50% of the food supply and are motivated not by human-centered persuasion strategies but by events that more or less scare people into action. Either way, greatly increased self-empowerment and security would result, which would add up to a considerable net benefit for the country.

Stay tuned for what will likely be the next three posts: The global food system in turmoil; How gardens supply 50% of Russia’s food; and The self-sufficiency beginner’s garden.

1Cunningham, W.P. and Cunningham, M.A. 2018. Environmental Science – A Global Concern. McGraw Hill.

0 Comments