The last few years have seen a veritable flood of books, articles, scientific studies, documentaries, and breathless pronouncements by leading food experts on the global food system and food insecurity. All adopt the unquestioning aim of trying to “fix” the industrial system. Pushed, as I described in the July 14 post, by the hand-wringing “need to” take worn-out “action steps” that can, could, should, ought to, would, or hopefully “promise to” stave off starvation. These hackneyed efforts reflect the proverbial rearranging of the deck chairs on the Titanic: they’ve never really worked at the largest scales over lengthy periods of time, and thus have even less chance of doing so in the future because of climate change.

To illustrate my own push—actually, pushback—I recently wrote a review of one of these books, Foot Fight – Misguided Policies, supply challenges, and the impending struggle to feed a hungry world (2025). The author is Richard Sexton, a Distinguished Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of California, Davis. To give him his due, here’s a quote from his book’s promo on Amazon:

“Feeding a growing world population is becoming more difficult in the face of climate change, pest resistance to traditional treatments, and misguided government policies that limit how much food ends up on our plates. Policies to support biofuels, organic agriculture, local foods, and small farms, and to oppose genetically modified foods all reduce food production on existing land. This leads to higher food prices, increased carbon emissions, and less natural habitat as cropland expands. Food Fight documents the challenges to adequately feeding the world in the twenty-first century and illustrates the ways in which contemporary food policies in the United States, Europe, and beyond imperil food security. Richard J. Sexton provides a window into the world of modern agriculture and food supply chains. He separates the wheat from the chaff to distinguish policies that will limit, or expand, the global food supply, and he explains how we can construct a food system that forestalls future hunger and environmental degradation.”

As you might surmise, he’s definitely in favor of fixing the industrial system, not with any form of sustainable agriculture—which he’d like to get rid of because it isn’t “efficient”—but by vaulting as much food “intensification” as possible to mega-farms, the bigger and sooner the better. Here is my take on that approach:

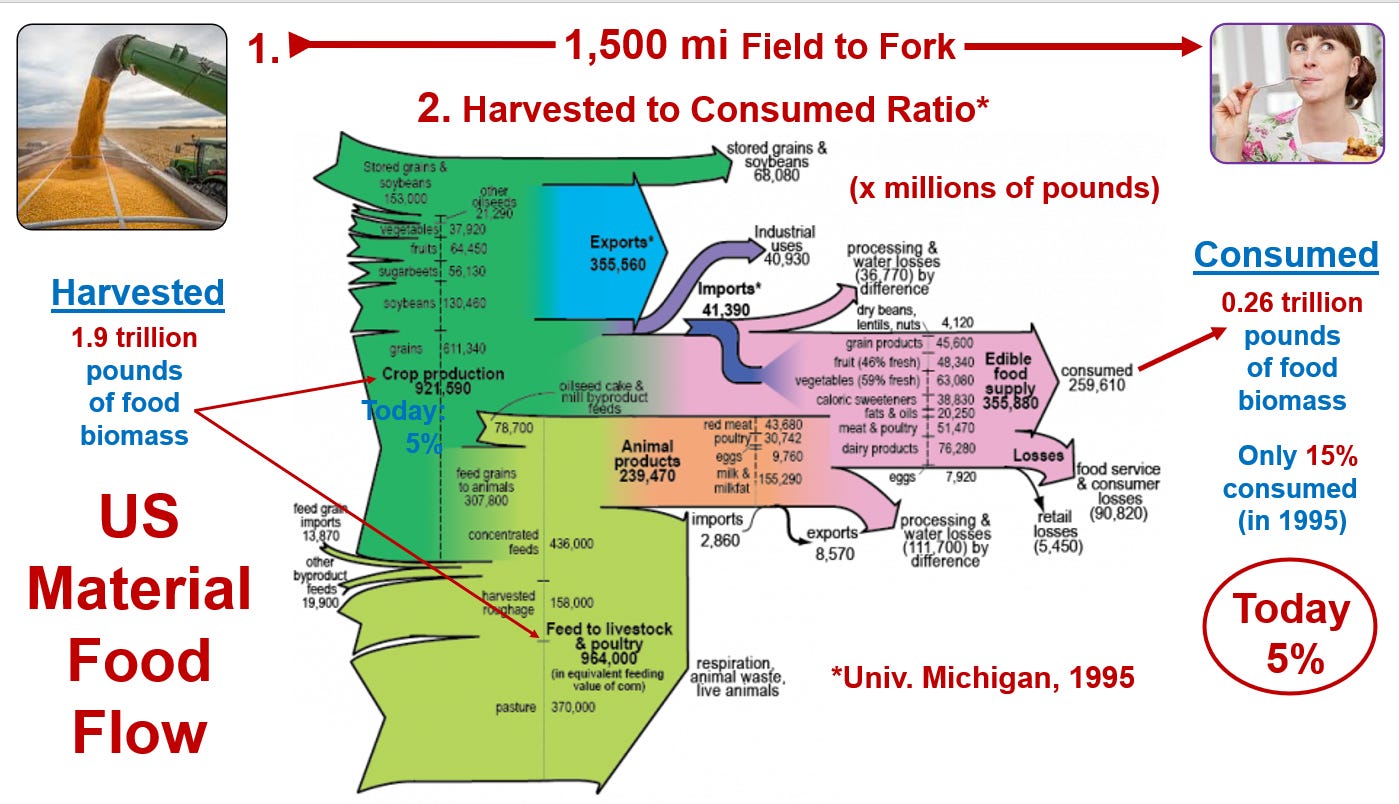

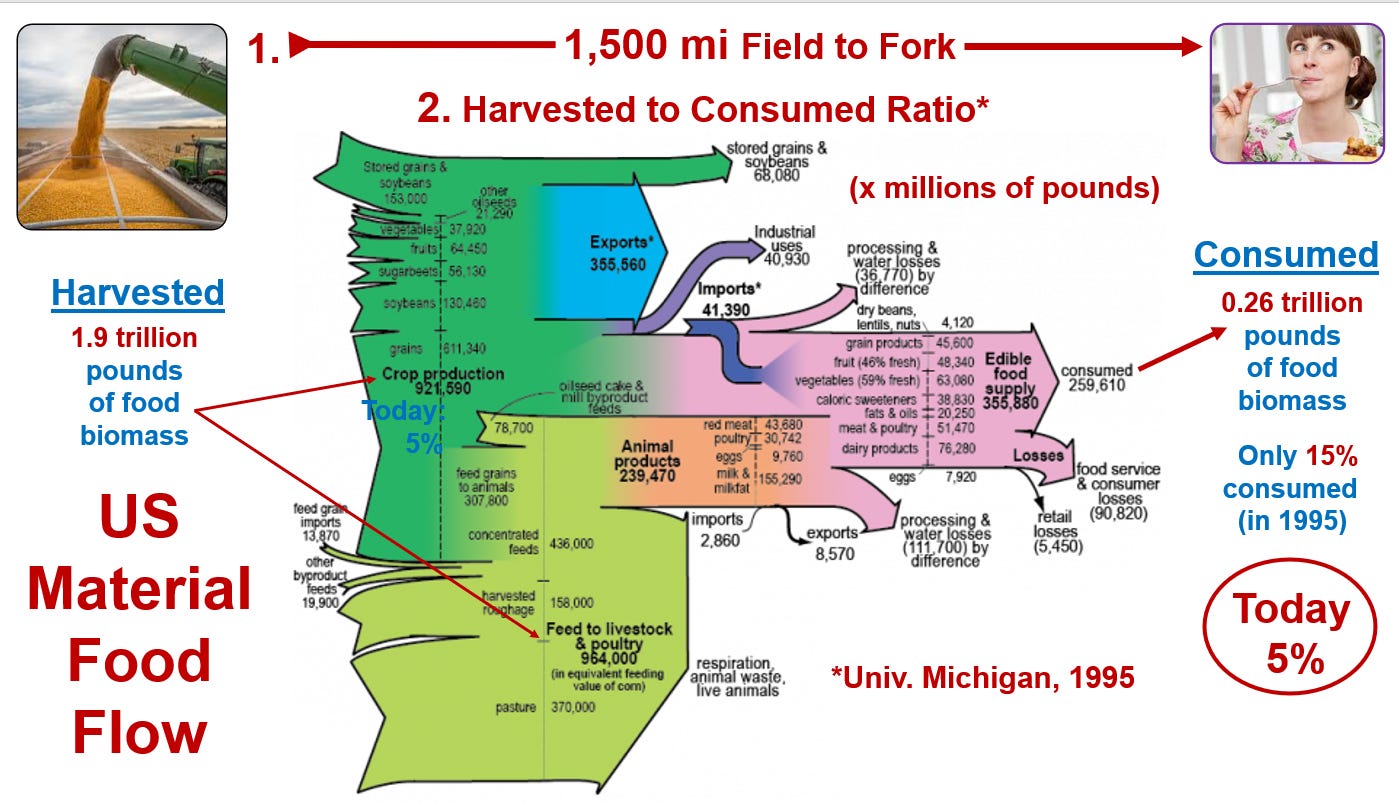

This book rests heavily on the invalid assumption that the industrial food system, of which the supposed gold standard accrues to the U.S., is amazingly efficient. Yet, as Sexton admits, “… farm products are bulky and perishable, and expensive to transport relative to their intrinsic value. This means they can’t practically be shipped long distances.” Correct. So how then could he portray our field-to-fork distance of 1,500 miles as efficient? (Answer: by ignoring full costs; see below) And contrary to what you might expect from his glowing accounts, a massive study by the University of Michigan’s Center for Sustainable Systems found that only 15% of U.S. food production (in terms of biomass) made it over that lengthy trek to the consumer’s fork1; how is that efficient? Notably, that was in 1995, before biofuels removed another sizable chunk from the food supply chain, and meat production—the least efficient part of the chain—increased by 45%. So that 15% figure is undoubtedly a good bit lower now. Again, how is that efficient?

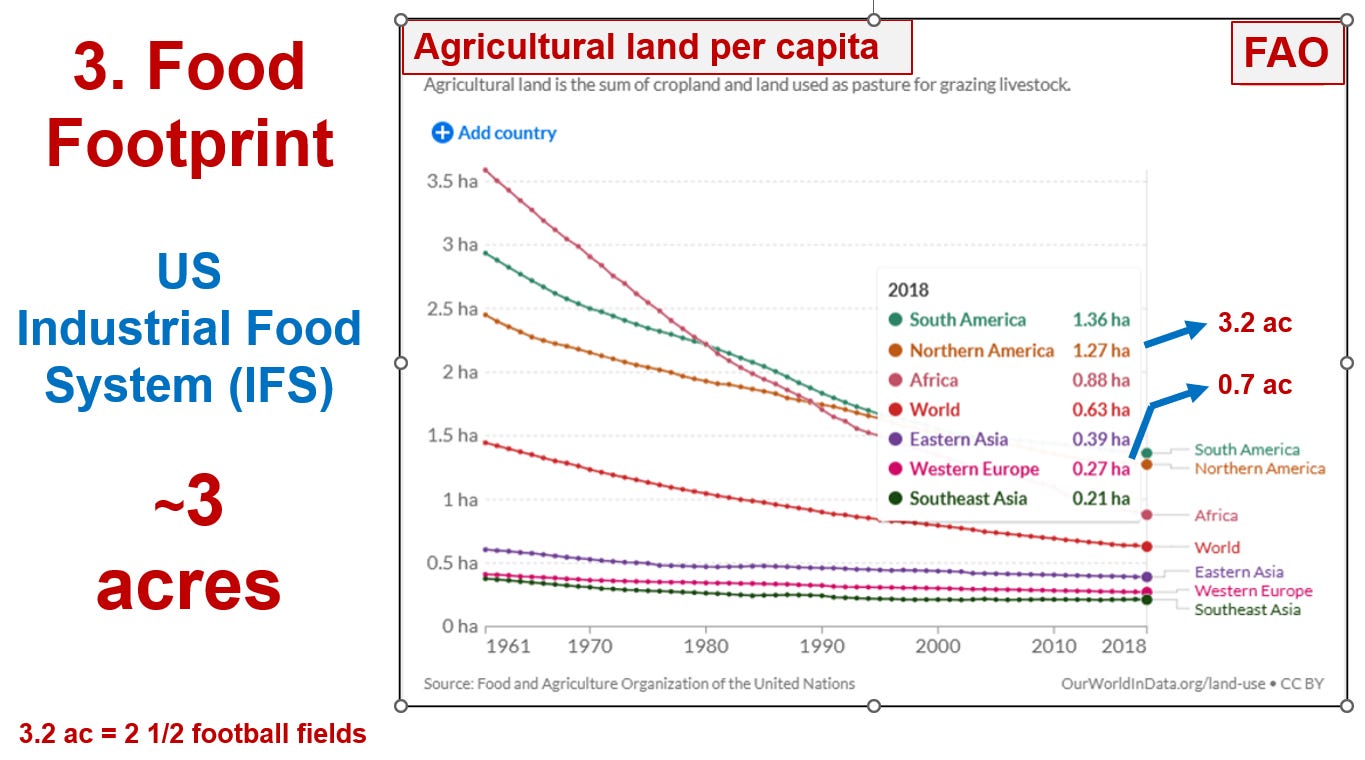

Moreover, the UN’s FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) reported in 2022 that agricultural land per capita (the food footprint) for the U.S. was 3.2 acres. In other words, it takes about three acres (independently verifiable) to feed the average American. Is that really an efficient use of land? By way of comparison, the FAO also said that western Europe, itself heavily industrialized, needed only 0.7 acres, or about one fifth as much land, to feed a European. So how is our 3.2 acres—which you’d expect to be the world’s lowest food footprint according to Sexton—so amazingly efficient?

That said, the most telling indicator of industrial food inefficiency is its enormous health, economic, social, and environmental external costs, which it foists off onto other cost-payers throughout our society. This amounts to some $2-3 trillion a year for the U.S., according to food system true-cost accounting mega-studies by the Rockefeller Foundation, KPMG International, the Milken Institute, the World Bank, and others. If you had a company half or more of whose operating costs, which were inflicting considerable external damage, were paid by a rich uncle so you could turn a profit, would you call that efficient? Of course not. Yet that’s the way our industrial food system works. In fact, it’s only able to function at all by throwing off much to most of its damaging operating costs

All of that is why Sexton’s claims—that our food system challenges are mainly due to bad information, practices, and policies that supposedly threaten our ability to free up enough land, to increase yields indefinitely, to feed ever more people—are altogether a moot point. He comes down especially hard on organics, which, even though it occupies only 1% of industrial ag land, he portrays as a threat to “intensification” of food production. True, organics, along with non-GMOs, regenerative ag, animal-friendly, and small and local farms, cannot compete price-wise with large industrial farms. But that’s because they don’t offload anywhere near as much of their operating costs as do the largest farms, and the industrial food system in general. Contrary to his repeated assertions, the cost premiums of small-scale ag are not due to inefficiency because of insufficient economy of scale—i.e., because the farms aren’t big enough. Rather, they’re because large scale has a corresponding large and effectively hidden advantage by not paying for the $trillions it racks up in external costs. In short, the vaunted industrial economy of scale is a hidden-costs economy of illusion.

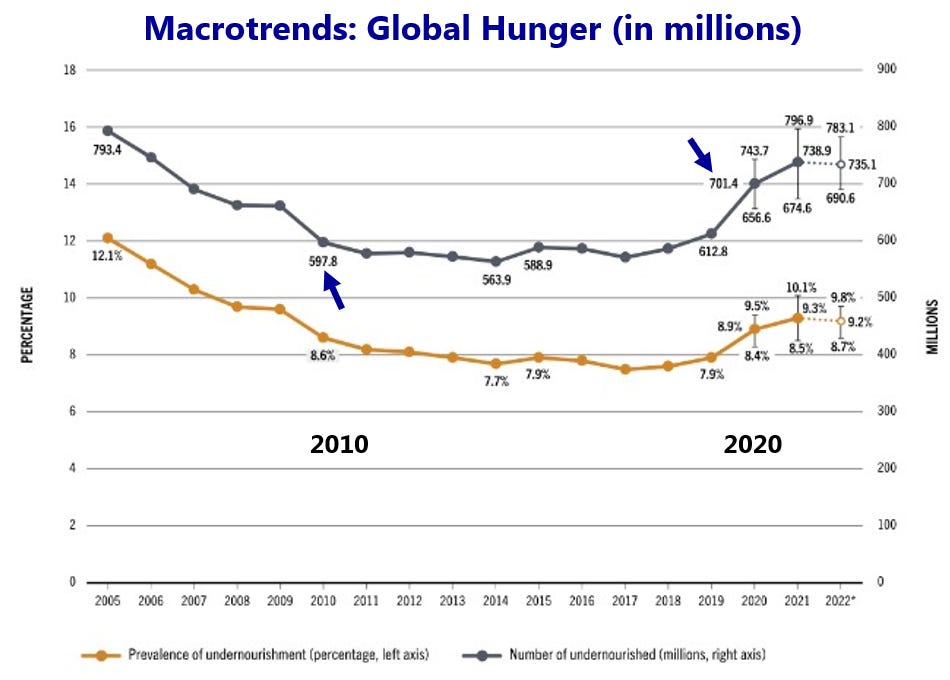

Even if it weren’t, from 2010-2020, the global population rose by one billion (14%), while crop calorie production rose by 24%.2 Yet during that time the total number of food insecure people also rose—by 103 million (from 598 to 701—a 17% increase).3 So even substantially increasing food availability in the usual ways—whether through yield intensification or other oft-prescribed but ineffectual means—is highly unlikely to reduce food insecurity over the longer term.

Fixing industrial food system strategies and policies is thus not the answer, in part because, as Sexton notes, once they get “baked in”, as all of the most consequential ag and food system policies are, they’re politically impossible to dislodge. His primary example is corn and soy re-directed to biofuels, but entrenchment applies to the rest of the food system as well. That won’t change as long as corporate profits are valued over the general welfare.

Fortunately—and unfortunately—there is an element that will soon force the industrial system to radically reconsider how best to produce and distribute food. (Which I agree won’t be slick new technologies, “climate smart” ag, regenerative ag, organics, small farms, or the like.) That element is climate change. When the Helene hurricane flooded the mountains of western N.C., many grocery stores—with their meager three-day, just-in-time supply of food—closed for weeks, thanks to the “efficient” food system. That, in turn, prompted FEMA to (belatedly) drop in pallets of MREs (meals ready to eat) by helicopter, and to employ pack mules to get food to people in places made otherwise impassible by washed-out roads and bridges. When ever-accelerating climate disasters get so intense and close together that the government—and the food system, and probably insurance coverage well before that—can no longer cope, then, and maybe only then, will we come up with a better plan.

Then again, does it make sense to wait until the proverbial s— hits the fan? What Sexton, as well as the rest of the agricultural economists and other food system planners, and all of us really “need to” do is go back to the drawing board. Avoiding relatively minor perceived threats to yield intensification—while remaining beholden to a fossilized food system deeply dependent on externalized costs—just won’t cut it. Especially now, with climate change bearing down on us.

1Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2025. “U.S. Food System Factsheet.” Pub. No. CSS01-06. https://css.umich.edu/publications/factsheets/food/us-food-system-factsheet

2Le Page, M. 2025. Fewer than half the calories grown on farms now reach our plates. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2493576-fewer-than-half-the-calories-grown-on-farms-now-reach-our-plates/

3World Hunger Statistics. 2025. Macrotrends. https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/wld/world/hunger-statistics

0 Comments