R U up for a little friendly yet globally-consequential controversy? Yes? Then read on.

Meet Michael 1

If you’re a foodie, you’re likely aware of Michael Pollan. Author of The Botany of Desire (2002), In Defense of Food (2009), and a steady stream of other books about food and the food system, he champions mostly whole, plant-based foods that are produced as genuinely natural as possible. In other words, he favors everything that ultra-processed food, and the way it’s industrially manufactured, isn’t. As a result, he advocates what’s widely perceived as sustainable and healthy—small-scale, local, organic, regenerative-type agriculture—all while avoiding junk food and being ultra-nice to the environment. Foodies love him; the industry, not at all.

Enter Michael no. 2

Michael Grunwald is a journalist who covers policy and national politics. His most recent book is We are eating the earth – The race to fix our food system and save our climate (2025). Like Pollan, he’s in favor of truly healthy food, and is no friend of the industrial system and the havoc it wreaks. Yet he notes that yields of organic agriculture average about 20% lower than those of industrial ag, thus requiring more land per person. And since land needs to be as productive as possible to feed 10 billion people by 2050, organic isn’t just less efficient, it’s also technically less environmentally friendly than industrial. In other words, the more land we use to grow crops, the more greenhouse gases we churn out, and the more we boost global warming. Which will destroy us if we don’t limit or reverse it.

So as Michael 2 puts it, the dilemma is how to feed the world without frying it, and industrial is ostensibly better positioned than organic to deliver that outcome. Yet fans of the healthier, more responsibly produced food favored by Michael 1 are horrified at the prospect of caving to what they see as the evil industrial lords plying their UPFs, plunder, and pollution while rendering 40% of the population obese.

And Michael 3 says . . .

Wait, what? Full disclosure, I was raised Catholic, and for those who may not be aware of it, when Catholic children reach a certain age, they are “confirmed”, in a special ceremony, for which they choose a “confirmation name” to add to their legal name. Well, I chose Michael, which made my religious moniker the rather grandiose David George Michael Fisher. So for the purposes of this post I hereby present myself as Michael 3. Just to insert a little camaraderie and lightness to offset the chippy emotional charge people sometimes bring to food and how it’s created.

Now, let’s back up. The goal in resolving the Michaels’ Food Dilemma is to simultaneously use less land, produce healthier food, preserve the environment, and reduce greenhouse gases. All four elements are essential, so they need to be revved up not just a little, but quite a lot if we’re to feed that 10 billion.

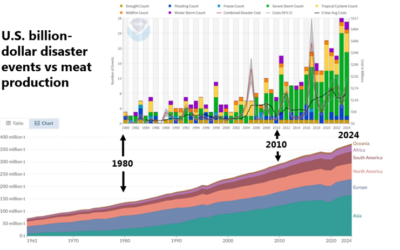

Michael 2 is correct when he says that industrial ag uses less land per capita than organic. However, that doesn’t mean it offers a way to solve the land use problem. Even we continued to use 20% less land than organic from here on out, it would still be nowhere near efficient enough to meet future food needs. A massive study of six staple crops over 12,683 regions reported that the global ability to adapt food systems is just 23% of what will be needed to feed the world in 20501. It further found that modern bread-baskets in wealthy countries will experience the greatest challenge to adapt. Surprised? You needn’t be, because even now the U.S. industrial system loses 50-85% of its harvest between field and fork, depending on whether the food is measured in terms of calories2 or biomass3, respectively.

Unfortunately, the more earth- and health-friendly organic route endorsed by Michael 1 would be even more challenged. Not only because of its lower yields, but even more because it currently turns out only a very small percentage of global food; in the U.S., it represents just 6% of food sales. Plus, if implemented it would add even more carbon to the atmosphere than industrial because of the yield lag. So it would have to make up even far more ground, no pun intended, than industrial would. Nor is it just organic. None of the theoretically more sustainable means of farm production, including the current rage, regenerative agriculture, could effectively ride to the rescue. Admirable and “pure” as they may be, they’re just not up to the job.

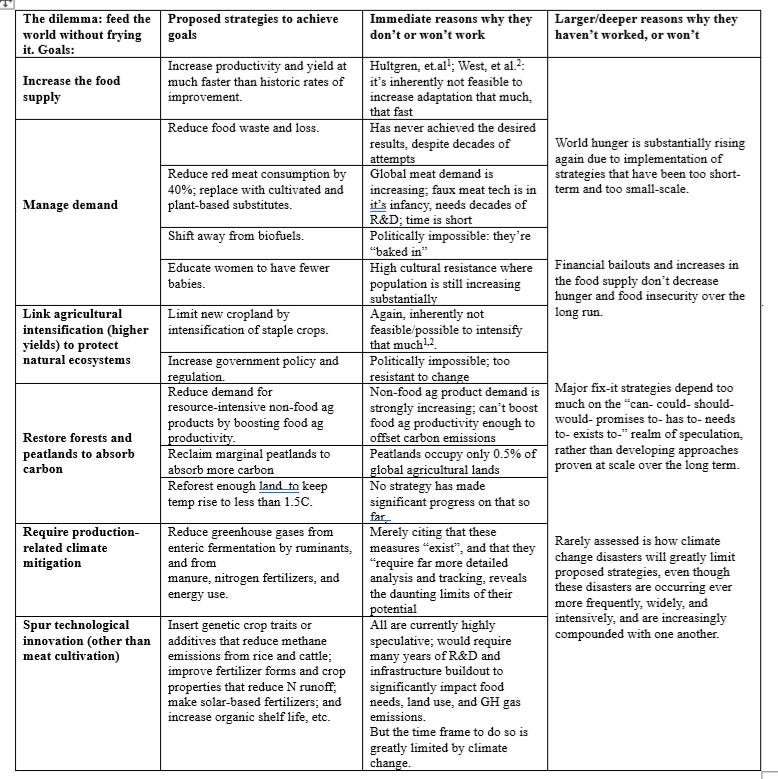

It will therefore come as a shock to hear that the farm, the centerpiece of the agricultural revolution and the resulting population explosion, is an idea that’s approaching the end of its capacity—all things considered—to adequately produce food at massive scales. Not that it ever really has, what with the food insecure long hovering in the hundreds of millions globally, and even 50 million in America. Of course, some still insist that all we have to do is reduce meat consumption, cut out excess waste, greatly increase yields, insert more tech, etc. My take is that those measures (including the Green Revolution) have either repeatedly fallen well short of resolving hunger at scale over the long term, or are based more on specious speculation than compellingly proven potential. (See the Addendum for a summary.) It is truly time to go back to the drawing board and come up with an alternative idea, which I believe is self-sufficiency gardens. Which, by the way, have been there all along, but whose value has gone mostly unrecognized.

A viable alternative

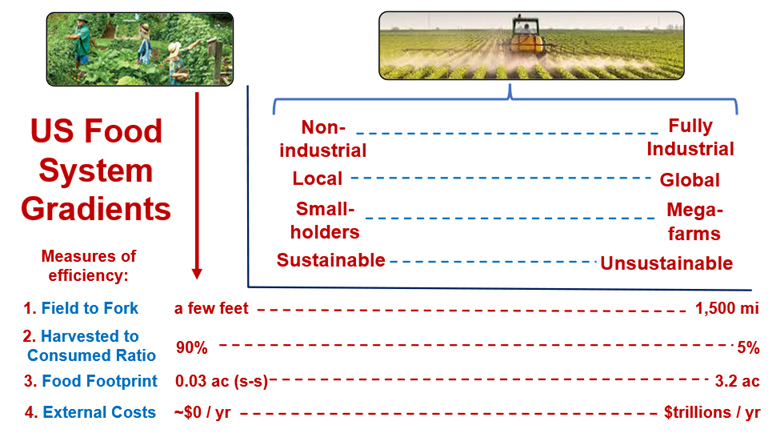

Globally, food production ranges from gardens to mega-farms along gradients of size, degree of industrialization, proximity, and sustainability. It also varies along continuums of efficiency according to four major measures thereof, as I’ve mentioned before:

The largest gardens overlap somewhat with the smallest farms, at least theoretically, along those parameters. Interestingly, I just came across an article on the concept of an “agrihood”, which is a working farm surrounded by single- or multifamily housing.4 Could it provide the neighborhood with most or all of its food? According to the story, it couldn’t possibly meet the community’s calorie needs, even though it could produce plenty of vegetables. So far, the few built-out attempts at this model have turned out to be unexpectedly complicated, which doesn’t surprise me. It’s another version of urban farming: potentially helpful, but yet to be proven at scale over time.

All told, it’s the much-needed increase in efficiency, by orders of magnitude in all four metrics, that enable self-sufficiency gardens to feasibly outperform farms by a wide margin. It’s not just a pipe dream; it’s backed up by solid evidence from individual to massive scales, as I’ve noted repeatedly. So a food system based on these gardens would honor and hopefully bring together the wonderful work of both Michaels while offering a proven way to simultaneously use much less land, produce healthier food, preserve the environment, and reduce greenhouse gases. All in service of meeting the daunting needs of the future. Again, not by completely replacing the industrial and local/regenerative models outright (we’ll have both for awhile yet), but by providing an alternative means of ensuring food security just when we need it the most.

1Hultgren, A. et al. 2025. Impacts of climate change on global agriculture accounting for adaptation. Nature. 642: 644–652. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09085-w

2West, P. 2025. Only half of the calories produced on croplands are available for human consumption. (Preprint) Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394005686_Only_half_of_the_calories_produced_on_croplands_are_available_for_human_consumption

3Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2025. “U.S. Food System Factsheet.” Pub. No. CSS01-06. https://css.umich.edu/publications/factsheets/food/us-food-system-factsheet

4Simon, M. 2026. What happens when a neighborhood is built around a farm. Grist. https://grist.org/cities/what-happens-when-a-neighborhood-is-built-around-a-farm/

Addendum

A summary of proposed strategies to reduce food insecurity while mitigating the effects of climate change, and why they don’t/won’t work

0 Comments