Throughout Ultra-Local, Full Circle Self-Sufficiency you’ve seen me refer to the research of Dr. Leonid Sharashkin, who reported that household gardeners in Russia produce 50% of the country’s food on just 3% of its agricultural land. And how his work demonstrates that the garden food system efficiencies I’ve revealed in my own research are scalable to many millions. Because of its bedrock importance, let’s delve into his story a bit more closely.

First, Sharashkin’s credentials. A Russian, he earned a Bachelor of Commerce and a Specialist in International Relations from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, followed by an MS in Environmental Policy and Natural Resources Management from Indiana University. He then headed the Conservation Finance and Economic Programme of the World Wildlife Fund, Russia while serving as editor of The Panda Times, Russia’s leading environmental magazine. Following an affiliation with the University of Missouri Center for Agriforestry, he received a PhD in Forestry there in 2008. He translated the eight-volume set of The Ringing Cedars by Vladimir Megré into English, and is the author of Re-creating a Garden Planet: Psychology of Humanity-Earth Megré Co-evolution (2009).

His dissertation The Socioeconomic and Cultural Significance of Food Gardening in the Vladimir Region of Russia, is equivalent to a 260-page book. It is extremely well-researched and engagingly written, but a bit much for the average reader to digest in toto. So I’ll just discuss his main themes and compare some of his most pertinent findings to the gardening and agricultural scene in the U.S., as well as my own research.

It’s important to note that much of the statistical information he cites comes from Rostat, the official government source of detailed records on many aspects of Russian life and industry, including gardening and commercial agriculture.

He has divided his work into three chapters: the first on the ancient and modern history of Russia’s family agriculture; the second on household agriculture in the Vladimir region of Russia; and the third on what he calls the invisible gardens.

Chapter 1 – Ancient roots, modern shoots: Russia’s family agriculture

The everlasting resolve

What impressed me most in this chapter is how fiercely, through all manner of upheaval and often brutal abuse, the Russian people have maintained their deep connection to the earth through their beloved gardens. Surprisingly, their battles with various autocratic figures and regimes—for over a thousand years—have been duplicated just since 1900:

Says Sharashkin, “The twentieth-century Russia saw wars, revolutions, repression, and famine; it was ruled by tsars, commissars, and presidents; it was orthodox and atheist, totalitarian, and “democratic”; it was feudal, capitalist, socialist, and capitalist again.”

Every one of those autocrats schemed to subvert garden bounty into a free source of food to compensate for non-existent or grossly inefficient state food production. Or (as is the case today) they either denied the gardeners any government assistance whatsoever, or refused to acknowledge their existence despite the extraordinary benefits they delivered to Mother Russia. (Hence the “invisible” gardens.)

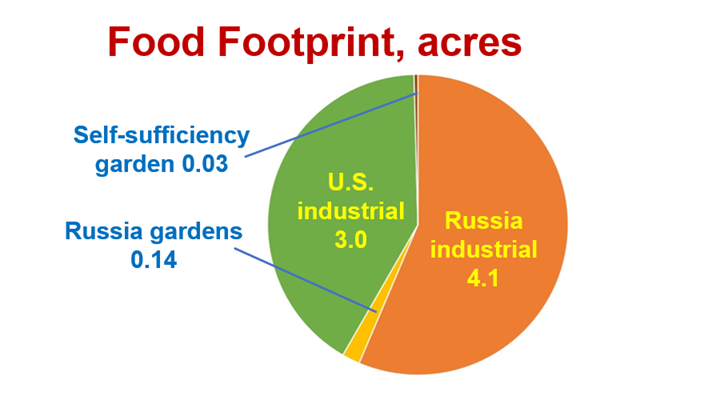

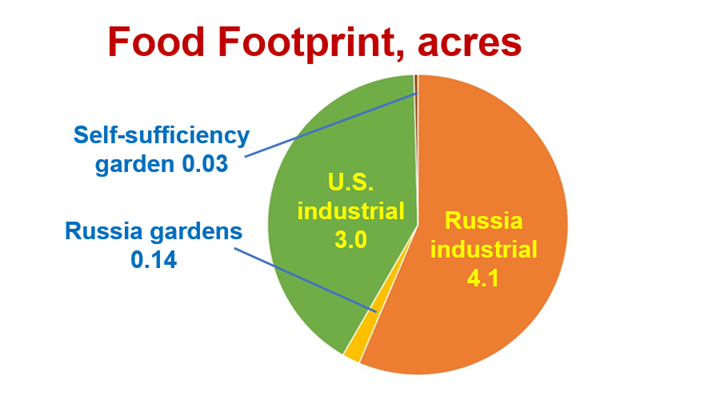

Food footprint

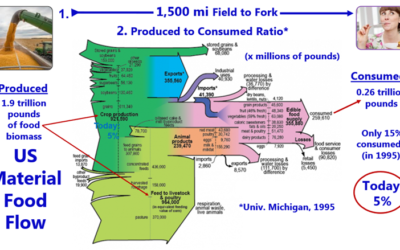

Remember the food footprint? If not, it’s the agricultural land needed to feed one person for a year. Here’s a comparison from Sharashkin, public sources, and my own research.

In other words, Russia’s industrial system needs (4.1/0.14) = 29 times as much land to feed one person as their gardens require. By contrast, the U.S. industrial system requires (3.0/0.03) = 100 times as much land as self-sufficiency gardens need to feed one. So although the footprints are different, both Sarashkin and I found that garden food systems are far more efficient than their industrial counterparts. Most important is that the Russian industrial data was compiled by their government for 72 million people (half of the country’s population in 2004).

It also happens that the U.S. and Russian industrial systems are about equally inefficient (with food footprints of 3.0 and 4.1, respectively), whereas my gardens are 4.7 times as efficient (0.14/0.03) as the Russian gardens. However, my data represents just three self-sufficiency gardens (even though their individual vegetable yields match garden yields of those averaged from five USDA field stations), compared to many millions of Russian gardens. Plus, there are other differences between what I, other American gardeners, and Russian gardeners do. As you will see.

What we each plant

It’s so amazing to me that I put all this emphasis on planting for a balanced diet with equal parts vegetables that are: starchy (for calories), “beany” (for protein), and watery (everything else—for additional vitamins, minerals, and fiber). By contrast, Russian gardeners focus on potatoes (53.1% of planting area) with the balance going to other vegetables, perennial crops, forages, grains, and beans — roughly in equal measure (between 10% and 15% each).

What?! How in the world do they get enough protein when beans are essentially an afterthought? Yet here’s where knowing a little history of Ireland might help. Prior to the late blight disaster of the 1840s, millions of their poor (but surprisingly healthy) people got almost all of their nutrition from potatoes. As I’ve mentioned before, per unit of dried weight, potatoes have as much protein as mother’s milk. Plus, they’re rich in vitamins, minerals, fiber, and resistant starch, and are naturally gluten-free, low-fat, and satiating. Eat enough potatoes and you can get by pretty well. Of course, Russian gardeners also produce some meat, milk, and eggs, though the amounts are still quite minimal compared to potatoes.

How many people garden, and what’s the dietary significance?

In 2019, 33% of all U.S. households had a food garden, compared to 66% of all Russian households in 2006. American gardens produce about 10% of the American diet by cash value, though only about 1% by calories. Meanwhile, Russian gardens produce about 50% of their country’s food by value (no data on calories).

What this means is that Russia is in a much better position than the U.S. to deal with an industrial food system collapse induced by climate change. Especially given that gardeners supply about 95% of the country’s potatoes. Besides, most of Russia’s gardeners already have a kind of permanent climate challenge, with, as mentioned previously, only a 4-month growing season compared to 8-9 months for Iowa.

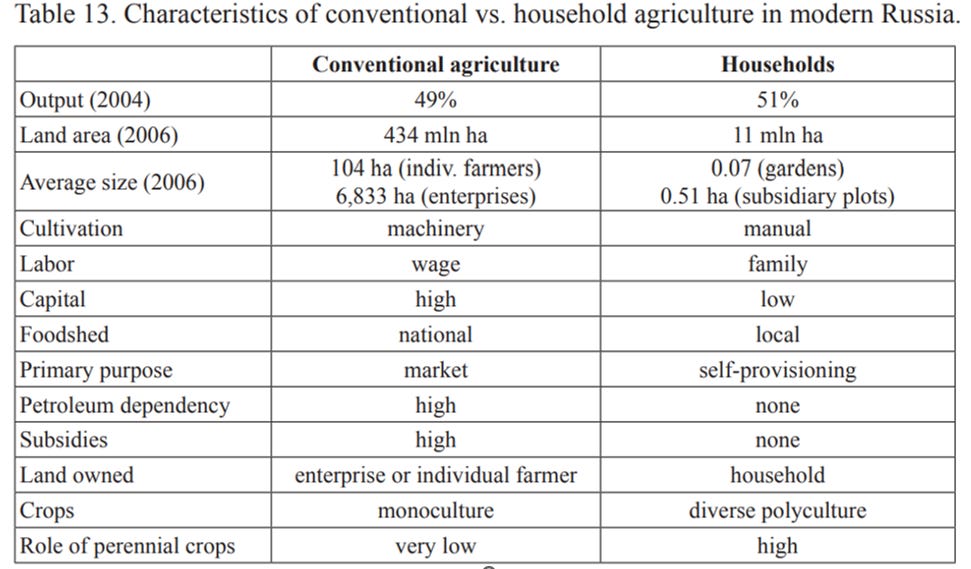

Comparing the two types of agriculture in Russia

Addressing the full significance of Sharashkin’s comparison of conventional agriculture and households would require a lengthy discussion, but I don’t think that’s necessary. You can get the collective import of it just by spending a couple seconds on each line of this table.

What is the primary purpose of gardening?

Here, Sharashkin references the legendary economist and statistician E.F. Schumacher, who held that land management should be primarily oriented towards health, beauty, and permanence. What a concept! The fourth goal—the only one accepted by the experts—producing food, will then be attained almost as a by-product.1 “On all these accounts,” says Sharashkin, “food gardening stands out as a holistic practice offering all of these economic, personal, social, and cultural benefits.”

This mirrors what I’ve said in my own way, namely, that even though self-sufficiency gardens are extraordinarily efficient and effective, their main benefit is not producing food but enhancing gardeners’ circles of connection to the earth, themselves, and others.[]

Sharashkin goes even further, observing that “. . . originally, agriculture was viewed as a spiritual path, and the most direct interaction with God was seen not in any formal religious ritual familiar to us today, but through cultivation of the soil.”

So, go to the soil instead of church to get to God? Maybe for some people that could work. Perhaps others would say why not both?

The conclusion

“The fact that self-provisioning is so universal, involves both rural people and urbanites, and plays a leading role in Russia’s agriculture, shows that the social institution of subsistence growing with its economic, social, and cultural characteristics has persisted from the time of the peasant economy to the present day.”

Chapter 2 – Household Gardening in the Vladimir Region

The purpose of this chapter was to go beyond the Russian government’s dry data to find out more about more about the family dimensions of gardening in Russia. To accomplish this, Sharansky zeroed in on the Vladimir region (“oblast”). Not only did he grow up there, he considered it to be representative of much of Russia, even though its area (11,200 sq mi.) and population (1.5 million) are less than 1% that of the country. Again, there is far too much data to even summarize what he found (dozens of tables and graphs), so I’ll just continue to describe a few representative nuggets, along with their context.

How does your garden grow?

Gardening is the hot thing in Vladimir oblast. A full 95% of all families either have a garden plot or contribute to or benefit in some way from the gardens of others, compared to about, as mentioned, 42% of U.S. households. Their plots average 3,726 square feet per person, over twice my 1,400. However, theirs often include—in addition to a wide variety of vegetables—fruit and nut trees as well as some grains and animals that need more room than my strictly vegetable plot. Interestingly, corn, which I love to grow, is not mentioned, neither for Vladimir nor the country as a whole, which is a major exporter of commercial corn.

About half of gardeners’ plots are next to their homes or within what’s considered to be walking distance for Russians (1.5 mi!), with the rest an average 12 miles away. Amazing. Anything over maybe 50 yards would be a deal-breaker for most Americans.

Sans commuting time, Vladimir gardeners average two and a half hours a day of tending, compared to my one. However, their growing season—like Russia’s as a whole—is only four months long, vs my nine months. Over their meager season, they average 290 hours per person, whereas I average 231, not all that different. They just have a lot less time to get in the work, as they are waaay up north, like Canada. But they do get it done, and obviously love doing it. Just like me. On average, Vladimir gardeners spend about $270 a year on gardening expenses per household, compared to $83 for American gardening households.

So the Russians have: 1) twice as many households gardening; 2) half as many months to get the job done; 3) garden plots more than twice the size of mine and on average a good bit further away from their house; and 4) expenses more than three times as much as Americans. All this while spending about 25% more time tending their gardens as I do. Despite, or maybe because of, these differences, they produce a far higher percentage of their country’s food by value (50%) than Americans do (10%).

Full disclosure, both the (U.S.) National Gardening Association and Sharanski report a fair number of other food gardening statistics, but I think I’ve covered the main areas for which there is data from both. That is, without going into excruciating detail.

Once again, what are gardens for?

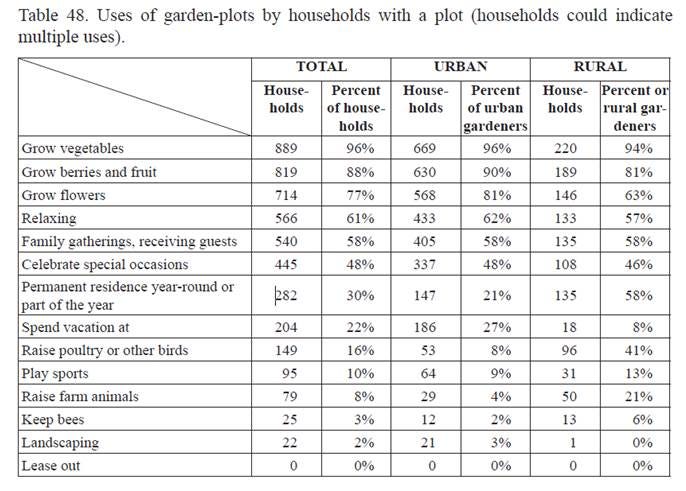

Why, to produce food, of course! Yet for Russian gardeners, that’s not even the primary reason they take up a hoe. Just look at all the other reasons they have gardens (Table 48). Now, Americans also value their gardens for several reasons other than providing food, but to nowhere near the extent that Russians do. As Sharashkin emphasizes again and again, food gardens are a major social and cultural feature of their lives. You don’t have to go very far down this list to find activities that you’ll rarely, if ever, see in American gardens.

Do you begin to see how and why gardens are a much bigger deal to the Russians than they are to us?

Chapter 3 – The Invisible Gardens

This relatively brief chapter laments the fact that despite doing so much for Russia, household gardens are all but invisible. That is, official Russian agricultural policy cannot even imagine a food system that doesn’t rely on large-scale industrial production that at best would try to commercialize whatever “surplus” household gardens produce. Even though they exemplify and convincingly document the benefits of gardens themselves.

I would add that the American industrial food system, along with the international system, are equally oblivious. A few months ago I had the chance, through an intermediary, to inform the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) of the UN about my approach. They said, Oh, we’re already doing that, and cited a page on their website describing essentially small-scale, somewhat sustainable but still farm-based agriculture. When I wrote back and described in some detail how distinctly different and demonstrably far more efficient a garden system is than even small-scale farms, I received no answer. It was invisible to them, too.

Nevertheless, the effort to inform persists. To further illustrate the value of gardeners’ connection to the earth, Sharashkin describes the work of Russian entrepreneur Vladimir Megré, who published the now nine-volume Ringing Cedars series. I think of these books as a form of folk documentary that “. . . advocate a return to the land and rural living as consistent with Russia’s traditional millennia-old lifestyle and the economic, social, cultural, and spiritual needs of human nature.”

As well, “Megré suggests that maintaining contact with one’s own piece of land and establishing a circular flow of matter, energy, and information between each family and their family domain’s ecosystem is important for both physical and psychological well-being.” This is a more concrete take on the benefits that Megré refers to.

What does it all mean?

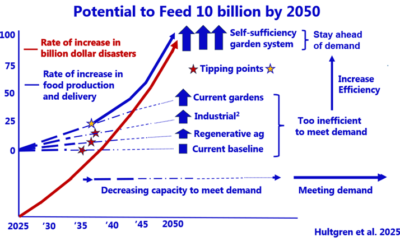

The overarching question is whether, compared to garden-based food systems, the gross inefficiency of the U.S. and Russian industrial systems is compelling enough to warrant adoption of garden-anchored food on a massive scale. Of course, that scale has already been achieved in Russia, but not for most of the rest of the world, as far as we know.

The irony is that we regularly see glowing news reports of—potentially, at most—15-20% yield increases that the media tout as “breakthroughs” that “promise” to “feed a hungry world” or save us from climate change disasters. Yet household gardening doesn’t just promise, it delivers. I emphasize how, via four measures of efficiency that self-sufficiency gardens are orders of magnitude more efficient than the U.S. industrial system. Similarly, Sharashkin focuses not only on garden production of 50% of Russia’s food on 3% of its agricultural land, but also on the extensive social, economic, and cultural benefits it confers. And that it’s been providing these kinds of advantages since antiquity.

For the near as well as longer-term future of food systems, proven orders of magnitude versus a few potential percentage points pretty much sums up the difference of this road not taken. Yet.

1Schumacher, E.F. 1973. Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Harper Collins.

0 Comments