What Is A Food Shock?

In case you haven’t been following the news lately, we’re currently facing what the media call climate change food shocks. These mega-threats will be triggered by already serious but increasingly extreme droughts, aquifer and surface water shortages, heat waves, fires, and floods we hear about almost daily now. Food system experts and climatologists call these events shocks because they’re likely to cause food shortages far wider, deeper, and sooner than most people would have thought possible five years ago. In other words, we’re about to be rudely shaken out of our “safe” food system paradigm.

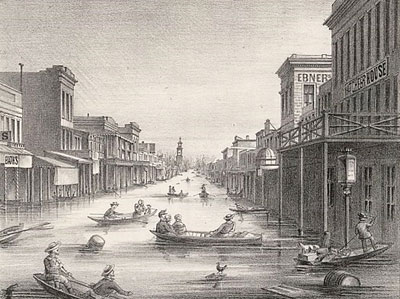

Geological records of the area reveal that floods like this have happened an average of every 123 years since the 1200s. Oops, that means we’re now about 62 years overdue for the next one. Imagine how that would play out today, when the Valley is home to 7 million people (projected to reach 8 million by 2030) and provides a fourth of all the consumed food in the US. When, not if, the next mega-flood hits, everyone living there will have to flee. Then, just as we’d be frantically searching for lodging for all those people, an enormous amount of food would have to be sourced from somewhere else. Quickly.

Although the other climate change shocks are arriving more gradually, they’ve already become so frequent we’re kind of in a “slowly boiling the frog” situation where, when we hear about the recent fires in the Texas panhandle that burned 2.7 million acres and killed 10,000 thousand cattle, we think, Oh, it’s just another one of those pesky calamities, not to worry. Only to later wake up, if we’re not careful, just before we’re dead by boiling.

Yes, boiling. Even though individual heat waves, droughts, and fires — exacerbated by water shortages — won’t be as massively catastrophic as a mega-flood, they will perilously eat away at the industrial food chain over the next few years.

So What Do We Do?

Nevertheless, there are signs that at least some more far-sighted food system- and climate-watchers are beginning to sit up and take notice. The industrial food system has certainly noticed, but its prescription is to just do more of what it’s always done: 1) improve efficiency through increased technology (now AI, robotics, GPS, drones, etc.); 2) push through more agri-food corporate consolidation; and 3) force more farmers to “get big or get out.” And they can point to past success there, at least for routine food production: since 1960 the amount of land it takes to feed one American (our “food footprint”) has dropped from about 6 to 3 acres, and the number of farms has decreased from around 3 to 2 million.

But can those strategies effectively prepare us for climate change shocks? Remember, the industrial food chain is huge, complex, deeply entrenched, and stretches 1,500 miles long from field to fork. About 95 percent of its material harvest drops out of the chain due to net exports; industrial uses; long-term storage; water, animal, and respiration losses; processing, and waste all along the way. Then there are those three acres it takes to feed the average American, all while racking up trillions of dollars a year in negative externalities, including massive subsidies. As if all that weren’t enough, it’s also facing a serious farmworker shortage, a growing backlash against UPFs, and sharply rising food prices. And don’t forget that it struggled to handle the relatively mild disruption of Covid. So in view of such glaring shortcomings, how likely is the industrial system to handle the enormous upset of a Central Valley mega-flood? Or for that matter, even the (so far) less menacing – but still constantly worsening – other climate shocks?

Nor will regenerative agriculture ride to the rescue. This rosy concept has been all the rage lately, but it’s basically just a rehash of proposals that various experts, research institutions, and NGOs have been proselytizing about for the last 30 years. Yet these more ecologically responsible farming practices have never generated more than about 1% of total US food sales. Why? Because they almost always result in significantly higher prices at the checkout counter. That puts them at a disadvantage since they can’t externalize half to two thirds of their costs the way the industrial system does.

The Self-Sufficiency Garden Food System

The Self-Sufficiency Garden Food System

Make no mistake, self-sufficiency gardens are different from the usual American veggie garden in ways that make them much more capable of addressing a food shock. First, the average garden is just 20’x30’ while a self-sufficiency garden is 35’x40,’ a quite manageable area about half the floor space of the average American house. Second, self-sufficiency gardens aim to provide a balanced diet in which watery vegetables are accompanied by protein- and energy-rich crops like beans and corn and, more for energy than protein, items like sweet potatoes, regular potatoes, and the like. By contrast, the top ten vegetables Americans grow are all watery and thus low in energy and protein. Plentiful vitamins and minerals, but you can’t live off them for very long.

The third difference is self-sufficiency gardens allow you to live solely from their bounty for an extended period of time – a week, or month, up to a year. This is what I discovered with my 2020 “Garden Super Size Me” experiment, in which I ate entirely from my garden for 30 days, then used the resulting data to compute how large a garden would have to be to feed me for a whole year, which was 35’x40’. So that’s the size garden I grew in 2021, and it produced 1,050 pounds of vegetables and 3,511 hearty servings, more than enough to last a year. The average veggie garden, again in sharp contrast, has no such capacity, largely because of the first and second differences.

Full disclosure, a self-sufficiency garden food system providing, say, at least 50% of our consumed food supply, will need to substantially expand the current garden support infrastructure. Think 50% is way too much to work toward? Even when you recall that, if the geologists are right, the next Valley mega-flood is 62 years overdue and thus quite likely to occur within the next 15 years? And that 40% of our consumed food comes from the Valley? And that, if the industrial food system’s response to Covid is any indication, it will lurch into chaotic gridlock when confronted with a truly major shock?

A robust, well-prepared self-sufficiency garden food system would feature either local businesses or national chains providing compost, mulch, greenhouses, garden supplies and equipment, gardening instruction/coaching, and done-for-you gardens for those unable to put in gardens by themselves. Fortunately, these structural enhancers would bolster employment in local economies. Of no small additional fortune: the expanded capacity would be essential to quickly ramping up to meet the shock of a national food shortage.

The overall point is that self-sufficiency gardens are much better positioned than the industrial system or regenerative/sustainable alternatives to generate a reliable food source for up to many millions of people. As genuine proof of concept, remember that 20 million US victory gardens provided 40% of the nation’s vegetables in the latter stages of WWII. Managed by amateur gardeners, with little training, on short notice. Add to that the amazing fact that household gardens in Russia produce 50 percent of the country’s food on just 3 percent of its agricultural land.

So adding it all up, if we want to prepare the nation for the coming food shocks, the best bet by far is not to try to shore up the industrial food system, but to go around it by galvanizing a full-out self-sufficiency garden food system. In other words, as a matter of national security,

Don’t Prep For Food Shocks By:

- Ramping up AI, drones, robots, GPS, and “precision” or regenerative agriculture

- To rescue a huge, cumbersome, entrenched,

- 1,500-mile-long food chain that

- Avidly promotes a diet of 60-75% unhealthy ultra-processed foods,

- Has a 3-acre food footprint,

- Incurs $trillions/yr in negative health, social, economic, and environmental costs,

- Depends heavily on subsidies, and

- Has a serious farm labor shortage

Rather, Pre-Strengthen:

- The existing garden food chain, just a few feet long individually, that

- Would feature, as self-sufficiency, healthy, balanced-diet gardens,

- A 0.03-acre food footprint,

- Generates no negative costs,

- Has proven, as victory gardens,

- To quickly, cheaply, and feasibly scale to feed many millions,

- Doesn’t depend on subsidies, and

- Has no need for farm labor

The Self-Sufficiency Garden Food System

The Self-Sufficiency Garden Food System

0 Comments