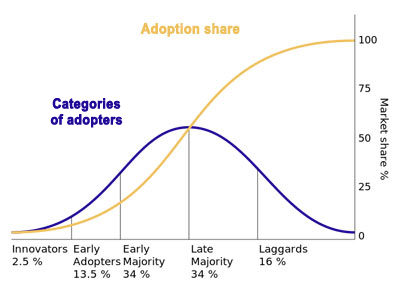

Rate of adoption

All successful innovations go through an adoption curve in which the new technology or idea reaches a critical mass, at which point it becomes self-sustaining. But not all innovations are successful. For instance, many have predicted that some form of innovative sustainable farming would reach that point, but together, those efforts have never exceeded about 1% of U.S. food production. Self-sufficiency gardens have a much greater potential to reach critical mass within a few years. Why? To emphasize it once again, self-sufficiency gardens have:

Demonstrated impressive scalability and efficiency, as in Russia’s household gardens providing 50% of the country’s food on just 3% of its agricultural land, and Nigeria’s production of 50% of its vegetables on 2% of it’s agricultural land.

Demonstrated impressive scalability and efficiency, as in Russia’s household gardens providing 50% of the country’s food on just 3% of its agricultural land, and Nigeria’s production of 50% of its vegetables on 2% of it’s agricultural land.- The capacity for quick implementation, as indicated by U.S. WWII victory gardens ramping up to 40% of the nation’s vegetable production on 20 million gardens within a couple years.

- An economic ease of adoption with minimal technology and training, again evidenced by victory gardens of not only the U.S. but also other countries, and Russia’s example as well.

Adoption strategies

The change agents who lead adoption may come from inside or outside of the pertinent community. Innovation is typically initiated by gatekeepers, followed by opinion leaders who further urge its adoption, and from there it spreads through the community.

The change agents who lead adoption may come from inside or outside of the pertinent community. Innovation is typically initiated by gatekeepers, followed by opinion leaders who further urge its adoption, and from there it spreads through the community.

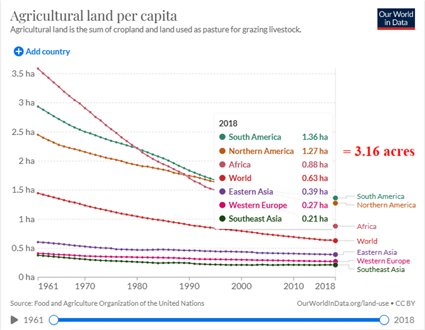

To prompt initial attention, adoption strategy should begin with vigorous publicizing of the startling fact that the IFS needs three acres to feed every American.

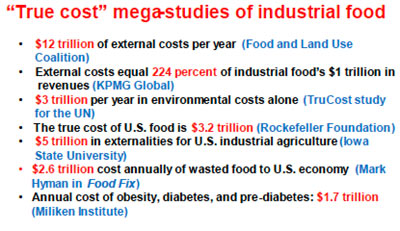

Following that should be the Factor One Hundred assertion, aided and abetted by the equally compelling facts that the GFS will avoid $trillions in IFS damage and externalities, and will generate far superior side benefits. To that end, implementation sub-strategies may include:

- Obtaining public support of highly-respected “foodie” (e.g., Michael Pollan, Marion Nestle) and environmental (e.g., Al Gore, Lester Brown) gatekeepers and opinion leaders, and from outside the community, personalities like Oprah

- Endorsement by the National Gardening Association and other gardening organizations

- Coverage in the mainstream and alternative press

- Enticing influential policy-makers to push the project forward, based primarily on enhanced national security threats (e.g., climate change, increasing natural disasters, and the coming California mega-flood*).

- Setting up an Early Adopter Challenge, enabled through a website or social media forums, of anywhere from one meal to a one year subsistence garden challenge: “How long can you live on the food you’ve grown yourself? One meal? A day? An entire week? A month? How about a whole year? Try and meet your comfortable self-challenged level and tell us about it.”

- Vigorously ramping up public awareness of the facts that, in addition to Factory One Hundred,

- Household lawns have enough area to accommodate gardens that can feed the 90% of the population that does not live in areas of 10,000 or more people per square mile.

- Note: this doesn’t mean that 90% of the population has to have home food gardens. If even a third of our total food supply were to be produced in self-sufficiency gardens, most likely partial subsistence gardens spread out over more than a third of households, it would bring enormous benefits to national well-being and food security.

- Ensuring that the process of adoption features an incubation period fueled by enduring communication networks. Social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and possibly even TikTok could be helpful, but only if they steadily build awareness. Viral flash-in-the-pan episodes that attract initial widespread attention but then quickly die out are not that helpful.

- Emphasizing direct word of mouth and example whenever possible, as inter-personal networks are far more effective (in terms of staying power, especially among people who are already connectivity-inclined) than less personal communication.

Benefits

Listed much more fully in No Trade-Offs

Individual level

- Better health due to both the food and the gardening activity

- Satisfaction resulting from self-empowerment

- Enhanced connection to the earth, self, and others

Collective level (local, regional, national, and global):

- When fully developed, self-sufficiency and food security

- As mentioned previously, mitigation or removal of massive health, economic, social, and environmental damage and externalities wrought by the IFS

The enhanced connectivity that accrues to individual gardeners is magnified when they are joined by many others in the local, regional, national or global community.

Costs

Individual

- Expenses of seeds, gardening, and preservation supplies, equipment, and energy, though many are a one-time costs that can be amortized over years

- Challenge of dealing with the unkempt—or even neat—appearance when located on the lawns of some communities, which may prohibit them due to claimed lowering of property values (Ironically, studies have shown that community gardens enhance a range of positive social indicators in the neighborhood, including property values.)

- Chemical pesticides and fertilizers, which some gardeners may use in even greater relative abundance than in commercial agriculture.

- Pollution from vehicle fumes if garden is located next to a busy street

- Note: the physical activity of gardening is not “labor” that must be financially assessed as if the gardener were a farm worker. If engaged enjoyably, knowledgeably, and in a way that is consistent with one’s physical abilities, the exercise and exposure to nature is not a cost but one of gardening’s main benefits, as it contributes substantially to good mental, spiritual, and physical health.

Collective

Campaigns to counter the $billions spent to keep the industrial narrative locked in place.

Campaigns to counter the $billions spent to keep the industrial narrative locked in place.- Subsidies, grants, tax breaks, and the like may help both individual gardeners and community gardens get started, but we have seen all too many

examples in the industrial system of how the recipients can come to depend on them indefinitely. This is how, for instance, we got the many different and costly forms of “farmer welfare.” Not to mention the costs of the same problem at the other end of the food chain, where millions of people depend on $120 billion a year of federal nutrition assistance just to survive. Nor the fact that the entire IFS depends on a kind of perpetual “externalities welfare,” in which other entities of society cover about two thirds of its true costs. Without those enduring financial care packages, the IFS simply could not afford to operate.

Accordingly, it should be explicitly required that any subsidy for home or community gardens come with an ironclad requirement that it be temporary. This is partly because one of the most valuable benefits is self-empowerment, which would be undermined by indefinitely continued dependence on outside financing. Ideal would be for newcomers to start up their gardens with their own resources, with the garden size commensurate with what they can reasonably afford, even if it’s initially quite small. Besides, starting small with gardens is much preferred to starting large, just to help ensure greater initial and then continued success with increasing size.

*Geological records show that over the last few centuries, mega-floods have sporadically inundated California’s Central Valley with about 15 to 20 feet of standing water. Five of these floods have occurred at intervals of about every 100 -150 years, with the last in 1861. Since that was 162 years ago, we are well overdue for another one. When it occurs, it will decimate about a quarter of U.S. food production and will drive a mass migration of the Valley’s population of 6 million, and possibly a few million more from outlying, lesser-flooded regions, to other parts of the country. Given its already gross production-to-consumption inefficiency, the IFS would not be able to make up for the food dearth. However, the GFS, given its already proven ability to supply as much as half of a large country’s food supply on very little land, could.

Sources:

Philpott, Tom. 2020, Perilous Bounty – The Looming Collapse of American Farming, and How We Can Prevent it, Bloomsbury Publishing; 256 pp.

Major, Payton, 2022, CNN. “A disastrous megaflood is coming to California, experts say, and it could be the most expensive natural disaster in history.”

https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/12/weather/california-megaflood-study/index.html

0 Comments