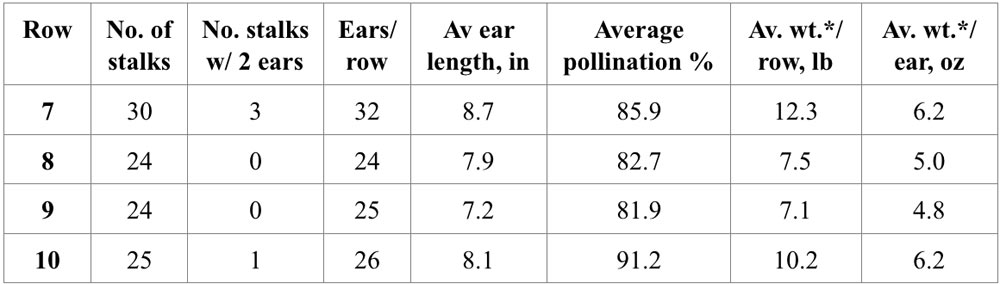

So, this year I planted about the same number of rows (four, each 12’ long, 3.5’ apart) and corn plants (100) as in 2019, but in about half the area (168 sq. ft.). By September I had harvested 37 pounds of dried, shelled corn, compared with 36 in 2019, which means the yield per square foot in 2021 was about twice that of 2019. So some success there, especially for row 7, which was the south-most row and therefore received the most direct sunlight.

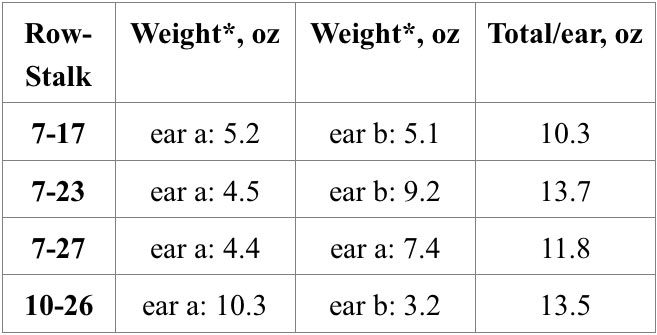

However, the two inner rows (8 and 9) were shorter, had fewer stalks, fewer ears per row, and were not as well pollinated as the outer rows (7 and 10); they also produced 35% less corn than the outer rows. In addition, the stalks grew to impressive heights making them susceptible to wind damage. Only four stalks produced two substantial ears per stalk (the rest producing just one, with nubbins here and there), and all four were in the outer rows. For those who like details, see the tables below.

Results of the 2021 corn plot (12’ x 14’)

*shelled, dried kernels

Plants with two ears per stalk (a and b)

*shelled, dried kernels

Altogether, it’s clear that despite doubling the yield per sq. ft., the plants were just too close to one another. I think the leaves of the inner rows especially were overlapped so thickly they were not getting enough light and were not allowing some of the pollen to reach the corn silks. For these reasons, in 2022 I will retain row length, number, and aisle width from 2021, but increase spacing between plants in a row from 7 to 10 inches. I’ll also use only seeds from the most productive ears (7-23b and 10-26a) of two-eared stalks from 2021. The goal is to increase production per stalk enough to more than make up for fewer plants. We’ll see if it works.

Bloody Butcher corn

Could commercial growers use Bloody Butcher? Of course not. Could I match my heirloom yield with commercial hybrid corn? I don’t see why not. Except I don’t see any reason to even try, given that some heirloom varieties are considerably more nutritious than most commercial varieties.

Further twists of the corn plot

Researchers are always looking for the Next Big Hope in commercial corn breeding. One of the most intriguing is nitrogen fixation in aerial roots to augment or even replace the heavy chemical fertilization that industrial corn requires. These roots resemble the prop roots at the base of the corn plant but extend well up the stalk, many never reaching the ground. An indigenous variety of corn from Mexico is reported to harbor nitrogen-fixing bacteria in a gloppy sheath around the aerial roots, so the race is on to breed that capacity into commercial corn.

Bloody Butcher corn prop roots with congealed mucilage

Notice, in the introductory image of the article’s video, how closely the height of this tall Mexican variety resembles that of my 2021 corn. Note also how the gloppy sheaths around the Mexican corn aerial roots resemble the congealed mucilaginous rings around the prop roots of some of my corn plants. Holy corn, am I sitting on a gold mine?

Not really. First, it will be extremely difficult to breed a multi-gene structural and physiological trait like that into commercial corn while retaining the many other traits essential to industrial cultivation and marketing. Second, although replacing nitrogen fertilizer with nitrogen-fixing corn root bacteria could reduce agricultural pollution somewhat, it would do nothing to address the $trillions in other collateral damages wrought by industrial food.

Another Big Hope is the claim that crop yields can be increased 20% by genetically engineering plants to “improve” photosynthesis. In as much as corn is the world’s leading crop plant, it’s among those being manipulated to achieve this end. The research is funded largely by Bill Gates.

The researchers claim that this effort can help save the hungry with more food. Never mind that the world already produces about 50% more food than it consumes, and that globally, obese people now outnumber the hungry. The U.S. also produces plenty of food to feed everyone in the country, yet almost 20% of the population is food insecure even though the government allots $122 billion a year to food assistance programs. So how could a 20% increase in corn yield help, either globally or nationally?

And even if such an increase could somehow help, just imagine how much more help would be rendered from three acres of gardens like mine, which can provide healthy food to 100 times as many people as it takes three acres of industrially produced food to feed one American a largely unhealthy diet.

It’s a worthy proposition to ponder.

Hi I’m so glad I came across your page about the aerial roots on your butcher red corn, I’m also growing seven stalks of it and they’re already 12 ft tall with several aerial roots growing around the base and upwards, but they still haven’t developed tassels or silk. Can you tell me when does this happen?